Article Post

07 Sep 2023

by James Ball

How Can the History Research Review Inform History Teaching in Your School?

History, like nostalgia, is not what it used to be. It’s better. Well, the teaching of it in England is anyway. That’s the conclusion of the recent government curriculum review that will no doubt make pleasant reading for teachers of history up and down the country.

Not only does the review state that the overall standard of history provision has improved since 2011, it also declares that the much-discussed gap in standards between primary and secondary is officially closed.

But the picture the report paints isn’t universally rosy and the best practice it identifies was not witnessed in every school.

So what were the things the government inspectors liked? What aspects of the current teaching of history did they criticise? And what could you do to incorporate more of what they identify as best practice into your history curriculum?

This article aims to support teachers and subject leaders in developing their curriculum and teaching methods in light of the findings from the history research review.

History Teaching in England - The Big Picture

The positives in this report far outweigh the negatives. The inspectors reached the conclusion that the “position of history in schools is much more secure now than it was 12 years ago”.

The fear of history melting away into generic humanities lessons also seems to have been allayed. Across the nation, the “trend towards the erosion of history as a distinct subject appears to have been reversed”.

This is the result of the tireless work of countless history teachers, department heads and school leaders. They are the ones who have designed, implemented and delivered strong history curriculums. They are the ones who took the decision to fight for the subject of history.

The History Curriculum Review - The Main Criticism

As we know, history is a verb. It is something you do. It is not simply a question of stuffing brains with ‘facts’ and dates to be recalled as proof of progress. But nor is it endlessly examining historical sources without understanding anything about the people and places who created them.

Much of the criticism in the report is directed at schools that fail to find the correct balance in their history curriculums. The best schools, it observes, equip their students with a “rich and connected knowledge of the past” whilst simultaneously giving them a deep understanding of the work of historians.

The report defines these two aspects of the teaching of history as substantive knowledge (what happened in the past) and disciplinary knowledge (how the past is studied).

Building Strong Substantive Knowledge in Your History Curriculum

The report does acknowledge the work done in the “large majority of primary and secondary schools” to improve the breadth and ambition of their history curriculums. Where they believe schools go wrong, is by creating a ‘core knowledge’ (information that is considered essential) that is too narrow.

Where the ‘core knowledge’ is insufficient, it is easy for misconceptions to take root. The report highlighted examples of the teaching of Rosa Parks, which is a popular topic in primary schools. Stripped of its wider context within the African-American civil rights struggle, some students believed that segregation only took place onboard buses.

This kind of misunderstanding is typical in schools where the substantive teaching of history is “disconnected or superficial or where there are significant gaps”. But it not only leads to an inaccurate perception of the past, it also inhibits students’ progress when it comes to disciplinary history too.

Alarmingly, the report observed that, “In around two-thirds of the schools visited, teachers focused on pupils forming their own judgements about sources and about the past, without first securing the knowledge they needed to do this in a meaningful way.”

It also noted, “… in nearly half the schools, teachers expected pupils to make their own judgements, for example on sources of evidence, without having developed the secure historical knowledge to be able to do this meaningfully…It often led to pupils having less secure knowledge of the past and misconceptions about the work of historians.”

This rush to form judgements before gaining enough substantive knowledge results in students having an inaccurate impression of both the past and what historians do.

The Generative Power of Substantive Knowledge

A key assertion of this curriculum review is that no learning of substantive historical knowledge is wasted. All substantive knowledge is useful. It doesn’t matter what period or location, it all helps to build a ‘hinterland’ of knowledge.

Substantive historical knowledge has what the report calls “generative power”. It provides new perspectives on existing knowledge, enables parallels to be drawn and contrasts to be made. By casting the curriculum net far and wide, “recurring terms, concepts and phenomena…help them to learn more easily about other topics.”

How Can You Include More Substantive Knowledge in Your Curriculum?

So how can you, as a teacher, build this hinterland of knowledge within your students?

Firstly, you have to ensure your curriculum is sufficiently ambitious. Avoid teaching the ‘bare bones’ and thinking it will be enough to cover a topic. As one school leader who is quoted in the report says, "Pupils already know about the pyramids [and the] 6 wives [of Henry VIII]; we want them to know about the ancient world, the Reformation”.

A few well-chosen books that broaden the scope of the topics you are teaching (such as Egyptian Myths or titles about the world the Tudors lived in, such as DK Life Stories Leonardo da Vinci) mean this is easily achievable and resourced.

Secondly, different students are gripped by different aspects of history and you’ve got to be ready to capitalise on this interest whenever it appears. This means having the resources on hand to enable a student to go down the particular rabbit hole that fascinates them. Or at least help them take the first few steps.

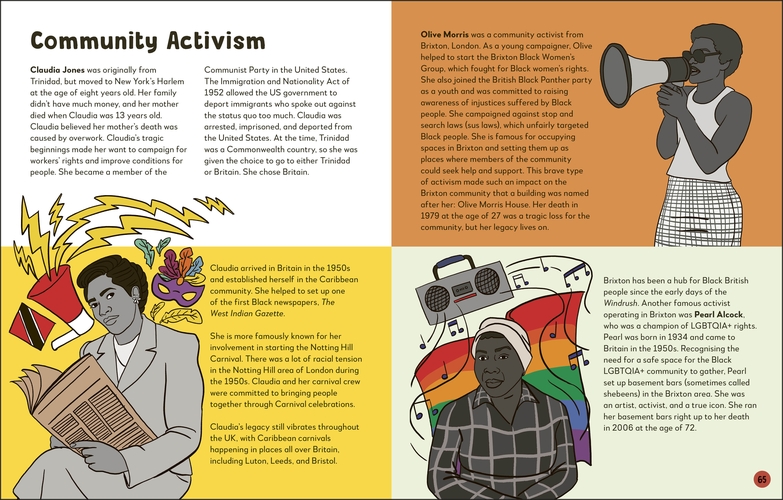

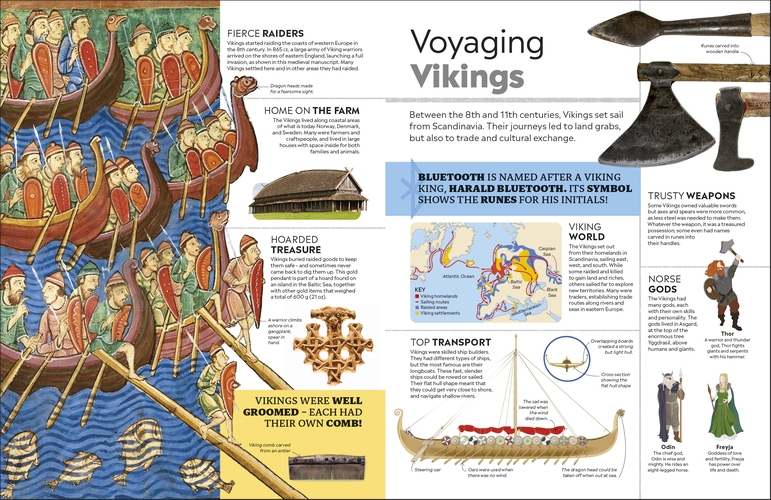

Investing in something like the Knowledge Encyclopedia History! means you will have nearly all bases covered, even in a room filled with the most curious of minds.

Providing a Macro and Micro Perspective on History

History is an incredibly complicated, intricate and intertwined thing, and that shouldn’t be shied away from. As the review notes, “Wherever teachers took the complexity of history seriously, pupils responded with enthusiasm. In many primary schools, for example, pupils were fascinated by the relationship between local, national and international developments. In many schools, pupils were gripped by the stories of individuals and became immersed in detailed study of other times and places.”

The exact nature of local history obviously varies from school to school but the stories of individuals will resonate wherever you teach. The DK Life Stories series covers a wide range of diverse people from history that are sure to capture the imaginations of students. Also, many of the Life Stories titles come with lesson plans and resources so they can be slotted straight into your schemes.

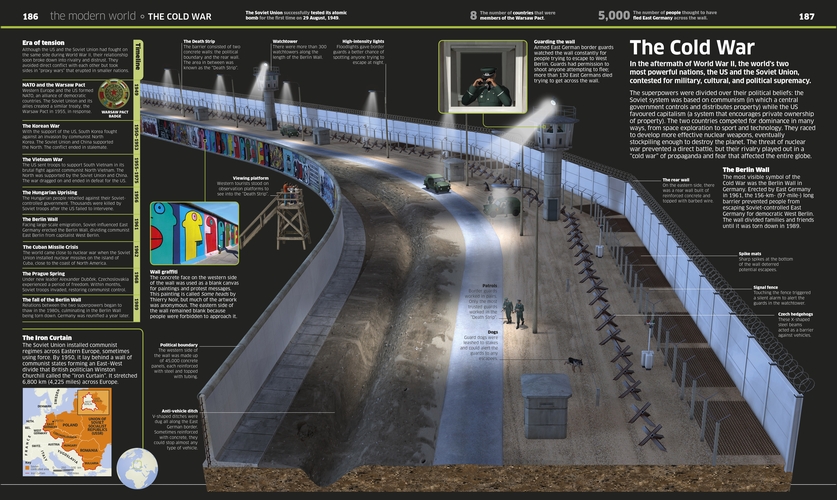

Local history can also refer to an area’s demographics as much as its physical location. The Black Curriculum series can help bring new perspectives to your schemes and it also comes with a host of free resources, activities and lesson plans.

Addressing a Lack of Depth in Disciplinary Knowledge

Although the review is overwhelmingly positive, its conclusions about the teaching of disciplinary knowledge are not a cause for celebration. In fact, it reports that many students fundamentally misunderstand what historians do and often mix them up with archaeologists.

The attempts to teach disciplinary knowledge are often undermined by a lack of substantive knowledge. This prevents students from being able to gain any meaningful insights from historical sources beyond what is superficial.

All teachers of history will be familiar with students dismissing sources as being useless because they are biased, so they won’t be surprised to see this mentioned in the report.

Teachers of Key Stages 3 and 4 might be forgiven for feeling slightly aggrieved when reading some parts of the review. The Nature, Origin and Purpose framework that is commonly used for evaluating the utility of a source has been dismissed as one of the “simplistic ‘tips and tricks’” used to teach disciplinary history. But, as many of the GCSE mark schemes require students to use this framework, it is perhaps not surprising that its use is so prevalent.

How to Improve Your Teaching of Disciplinary Knowledge

Schools that successfully taught disciplinary knowledge were credited with illustrating how historians use sources in a positive light. They emphasised what could be inferred from a source rather than immediately searching for reasons why its use was limited or why its provenance was unreliable.

This means exposing students to large numbers of historical sources so they become well-practised in making inferences. It also means examining the work of published historians and examining how they have reached their interpretations and judgments about a historical event.

The Eyewitness series of books is packed with historical sources on a wide variety of topics and periods. This is an ideal way to enable students to improve their skills in drawing inferences. It also exposes pupils to the enormous variety of physical sources that exist and gives them an insight into how historians go about their work. The latest Eyewitness title, DK Eyewitness Encyclopedia of Everything is the perfect resource for your classroom or library if you’re looking for an all-encompassing, visual guide to key moments in history, science and nature.

Building a Balanced History Curriculum

Enormous strides have been taken since 2011 and, as history teachers, we should be enormously pleased and proud that our subject has been judged to be in such rude health. The hard work that was put into designing, developing and delivering new curriculums has been officially recognised. More importantly, it is “…having a significant impact on the quality of education that pupils receive in history”.

But there is obviously room for improvement. Like so many aspects of teaching, identifying exactly how to improve comes down to an individual’s professional judgment. Incorporating just the right amount of substantive knowledge and disciplinary knowledge in the curriculum is a judgment call. And the success of history in your school will, to a large degree, depend on how successful you are in this.

What is crystal clear, however, is that no historical learning is wasted. African, American, European or Asian. Ancient, modern or medieval. Substantive or disciplinary. It all feeds imaginations, fills in the blanks and fires synapses. And where’s the best place to access all this knowledge? The answer to that is straightforward.

Books.

James Ball has over 20 years’ experience as a teacher and faculty lead of humanities. He is also an author, content creator and copywriter, who has been writing highly successful educational textbooks for over 15 years. His books have been aimed at a variety of Key Stages but always place emphasis on accessibility and engagement. Whilst continuing to write textbooks, he also creates scroll-stopping, SEO-infused blogs and reports for Edtech companies, marketing agencies, industry magazines and educational publishers.